The Contributions of Business Faculty at Unionized Public Universities

On November 9, 2023, OU AAUP hosted a panel discussion on the contributions of business faculty at unionized public universities.

The panelists

Rudy Fichtembaum, Emeritus Professor of Economics, Wright State University, Former President of AAUP

Howard Bunsis, Professor of Accounting, Eastern Michigan University, Past Chair of the AAUP Collective Bargaining Congress

John Martin, Professor of Management, Formerly AAUP Chapter Grievance Officer at Wright State University

You can watch the video of the full event at this link.

Salary comparison data

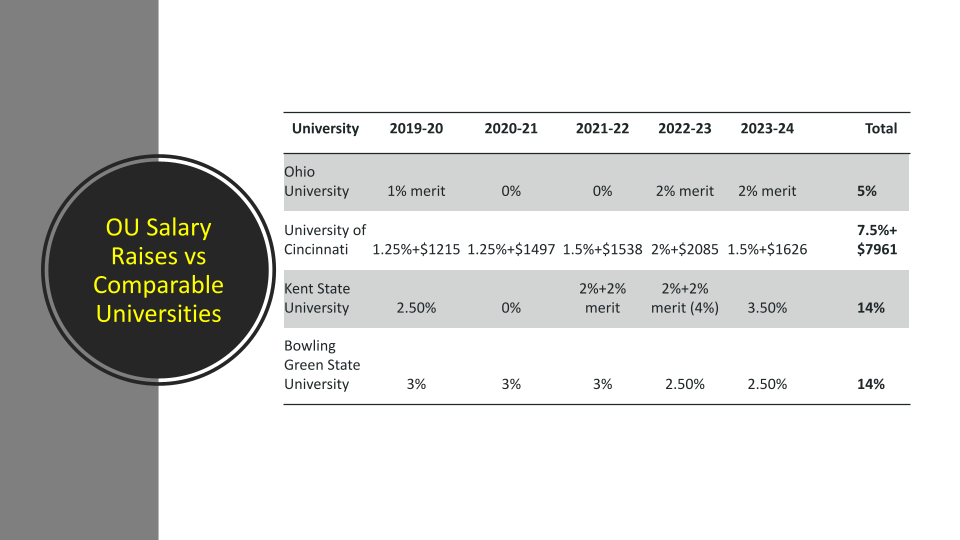

OU’s James Mosher, Associate Professor of Political Science, shared some comparative data on salary raises at OU and unionized public universities in Ohio.

Since 2019, OU faculty have received a total of 5% salary raises (without taking compounding into account). Unionized faculty at other public universities in Ohio have received 14% over the same period of time, largely due to cost-of-living adjustments they have negotiated in their collective bargaining agreements.

Because of the differences in salary raises, OU faculty is losing out on $50,000-$70,000 of salary over a seven year period.

Summary of Q&A

Q: From the perspective of business faculty at your institutions, what were some of the most compelling reasons for unionizing?

Written Response from panelist John Martin: 1) business faculty salaries will generally grow faster in absolute dollar terms than most other faculty; a 3% raise on $120,000 is better than a 3% raise on $80,000. 2) many union contracts allow faculty to obtain a competitive offer from another university and then have the university match it (i.e., another university offers a faculty member $10,000 more per year; the current university can match that). 3) Incoming faculty negotiate their starting salaries completely independent of the contract (aside from minimum salaries)—incoming faculty will get competitive starting wages commensurate with other similar business schools.

Q: Do you see any disincentives for productivity in research or teaching under a faculty union?

John Martin: I was never MORE productive…the most productive part of my career. This is because I knew exactly what was expected of me for teaching, research, and service. I was able to secure course releases for superior scholarship (i.e., publications).

Q: Could Howard talk a bit more about negotiations for the “Super Professor” promotion? I think that concept would appeal to many business faculty at OU.

[Initial discussion of this topic can be found beginning at 22:10 in the recording, and Howard’s response to this specific question begins at 38:19 in the recording.]

Howard Bunsis: The “Super Professor” promotion is a promotion beyond Full Professor with corresponding pay increase similar to the increase from Associate to Full. The position was created after three contract negotiation cycles because the University was hiring fewer Assistant Professors, and many faculty had reached the level of Full Professor. The position is a win-win for the University and faculty. The University is able to encourage research productivity and teaching excellence among Full Professors and to retain the most experienced and most research-productive faculty by creating new financial incentives for those faculty. Faculty get financial rewards for continuing to be high-achieving in research and teaching. There is no way this position would have been created without the bargaining power and advocacy of a union.

Q: How would you answer the question that many business faculty have asked: Doesn’t a union just add another level of “red tape” to an over-burdened faculty member’s life?

John Martin: On the contrary! Our elected team of faculty representatives negotiated comprehensive collective bargaining agreements and the resulting contract made it much less burdensome for me to focus on teaching and research. Regarding raises and research funds, for example, faculty members no longer had to discuss individual arrangements with their chairs and deans (on an often ad hoc basis). Rather, the contract spelled out those very arrangements in sufficient technical detail. Having this publicly-known framework of research allocation and decision-making is actually a huge relief for faculty members in terms of pursuing their job-related responsibilities (in a stable and transparent institutional environment).

Q: I’m worried about a faculty union handcuffing our administration, especially in times of crisis when we need flexibility to reduce workforce and cut budgets. How do unionized campuses fare when enrollments tank?

John Martin: This is covered in the contract (re. “retrenchment”) and the subject matter of the negotiations between administration and collective bargaining unit. Retrenchment language is common in all these contracts. However, and most importantly, the crucial difference with a union is that there is a clearly laid-out and transparent process (as part of the antecedently-determined contractual arrangements). First, such a contract spells out the conditions under which “financial exigency” can really be used as the justification for layoffs. Second, unions ensure that severance payments are of a reasonable magnitude and an enforceable entitlement (not an arbitrary hand out).

Q: How are collective bargaining teams constructed? I appreciated John’s remarks about the skill sets business faculty can bring. Are there business faculty on your bargaining teams?

Rudy Fichtenbaum: The details of this process are always up to the local union but there are common ways and procedures of, for example, nominating the “negotiating team.” Ordinarily, the executive committee of the union (all are elected by members) appoint other union members to serve on the negotiating team. At Wright State, for example, there was a “chief negotiator” who was appointed that way. (Rudy himself served as CN for a long time, 1999-2015). This should be an appointed position because if negotiations don’t go well, the executive committee should have the ability to replace members of the negotiating team. In general, the union constitution and the bylaws lay out the process for appointing the teams. One important goal that should guide this process: A smart executive committee is a diverse committee, representing all the different needs and preferences in the distinct academic units, schools, and colleges of the university. A good negotiating team will then reflect this same diversity, ensuring that all faculty members’ and units’ needs and interests keep informing the negotiations with the administration.

Q: Based on your experience and in talking with your colleagues in business schools, are there any downsides to being part of a faculty union?

John Martin: I can’t think of anything. Having a faculty union is a great option for faculty. What I like about it is that we have bylaws that were developed by faculty and approved by the administration. These codified criteria for promotion and tenure.